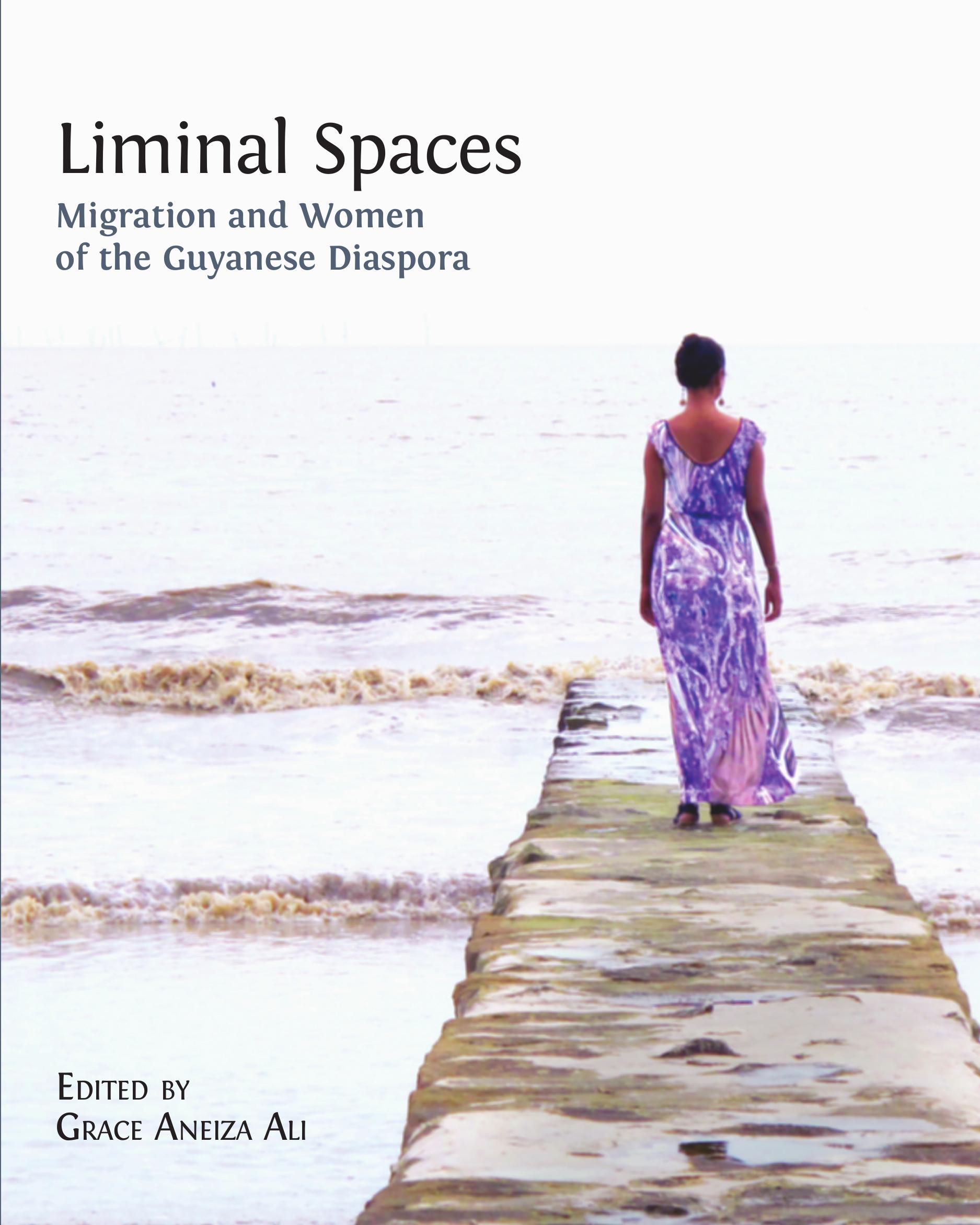

New book announcement: Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora, edited by Grace Aneiza Ali. Please find the description, the table of contents, and the chapter descriptions below. The book can be accessed (free in PDF form at the time of this posting) here.

ABOUT THE BOOK:

Liminal Spaces is an intimate exploration into the migration narratives of fifteen women of Guyanese heritage. It spans diverse inter-generational perspectives – from those who leave Guyana, and those who are left – and seven seminal decades of Guyana’s history – from the 1950s to the present day – bringing the voices of women to the fore. The volume is conceived of as a visual exhibition on the page; a four-part journey navigating the contributors’ essays and artworks, allowing the reader to trace the migration path of Guyanese women from their moment of departure, to their arrival on diasporic soils, to their reunion with Guyana.

Eloquent and visually stunning, Liminal Spaces unpacks the global realities of migration, challenging and disrupting dominant narratives associated with Guyana, its colonial past, and its post-colonial present as a ‘disappearing nation’. Multimodal in approach, the volume combines memoir, creative non-fiction, poetry, photography, art and curatorial essays to collectively examine the mutable notion of ‘homeland’, and grapple with ideas of place and accountability.

This volume is a welcome contribution to the scholarly field of international migration, transnationalism, and diaspora, both in its creative methodological approach, and in its subject area – as one of the only studies published on Guyanese diaspora. It will be of great interest to those studying women and migration, and scholars and students of diaspora studies.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Notes on the Contributors

Introduction: Liminal Spaces

Grace Ali

Part I: Mothering Lands

Grace Ali

1. Surrogate Skin: Portrait of Mother (Land)

Keisha Scarville

2. Until I Hear from You

Erika DeFreitas

3. Electric Dreams

Natalie Hopkinson and Serena Hopkinson

Part II: The Ones Who Leave… The Ones Who Are Left

Grace Ali

4. The Geography of Separation

Grace Ali

5. Transplantation

Dominique Hunter

6. Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women

Khadija Benn

Part III: Transitions

Grace Ali

8. So I Pick Up Me New-World-Self

Grace Nichols

10. Memories from Yonder

Christie Neptune

11. A Trace | Evidence of Time Past

Sandra Brewster

Part IV: Returns, Reunions, and Rituals

Grace Ali

12. Concrete and Filigree

Michelle Joan Wilkinson

13. A Daughter’s Journey from Indenture to Windrush

Maria del Pilar Kaladeen

Postface: A Brief History of Migration from Guyana

Grace Ali

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

ABSTRACTS:

Part I: Mothering Lands

1. Surrogate Skin: Portrait of Mother (Land)

Keisha Scarville

Artist Keisha Scarville spent her childhood raised in Brooklyn where her parents, along with so many other Guyanese immigrants, migrated and settled after leaving Guyana in the 1960s. In her photography essay, ‘Surrogate Skin: Portrait of Mother (Land),’ Scarville reflects on her portraiture series, ‘Mama’s Clothes,’ an homage to her late mother. In the portraits, Scarville embodies her mother’s dresses to evoke her connection to Guyana. In both her prose and portraits, Scarville grounds herself in her mother’s place of birth of Buxton (Guyana) and her neighborhood of Flatbush (US). The lush, organic landscapes in these images, shifting between Guyana and the US, hold emotional and geographical significance: they capture the artist and her mother’s dance between transient spaces. Grappling with ‘a sense of displacement and an internal fracturing’ after her mother’s passing, Scarville looked to her ‘mama’s clothes’ of bright colors, strong prints, and long flowing fabrics for meaning. She drapes and layers her body in her mother’s clothing as well as fashions masks and veils to cover her face, which is always obscured. In merging her body with her mother’s clothes, Scarville marries both time and space—two generations, two homelands, and the complexities in between.

2. Until I Hear from You

Erika DeFreitas

In an artistic practice steeped in process, gesture, performance, and documentation, Canadian-born artist Erika DeFreitas generously mines her family archive of photographs and letters throughout her oeuvre. In her art essay, ‘Until I Hear from You,’ she turns to old letters and photos sent from Guyana to construct memories with a grandmother she’s never met and to piece together a motherland she’s never known. Her grandmother, a skilled baker in British Guiana in the 1950s, passed down the practice to DeFreitas’ mother who then migrated to Canada in 1970. In sharing her family album, DeFreitas illustrates how the act of passing on sacred crafts through two geographies and three generations of DeFreitas women has shaped her connection to Guyana. In her essay, she expands on how she uses cake icing—perfected so beautifully by her grandmother that she taught classes in cake décor to the women in her neighborhood—as an important symbol in her work as well as in her poetic language. The icing is both material and process—meant to decorate and to preserve. DeFreitas leaves us to ponder the question: Even when we commit to preserving a motherland’s memories, rites, and traditions, how do we navigate the inevitable loss that pervades?

3. Electric Dreams

Natalie Hopkinson and Serena Hopkinson

In a series of letters that read as intimate journal entries, letters that could easily belong to familiar collections like ‘Letters to My Younger Self,’ letters that unveil deep untold secrets and desires, mother and daughter Serena Hopkinson and Natalie Hopkinson reveal the great love and admiration that abides at the core of their relationship. It is a mother-daughter bond that has seen several migrations across three countries: Guyana, Canada, the US, and many returns and reunions in between. Guyanese-born Serena Hopkinson migrated to Toronto in 1970 as a young bride who would soon embark on building a family of her own while navigating the terrain of being an immigrant in Canada and later the United States. The Hopkinson family life was one in constant transition, defined as being ‘on the move.’ The letters the Hopkinson women write to each other in ‘Electric Dreams’ are symbolic postmarks of the places they have borne witness to, survived, and thrived: Pomeroon River, Guyana; Edmonton, Canada; and Florida and Washington, DC, United States. Like so many immigrant families who have left Guyana, a series of arrivals and departures in search of ‘a better life,’ took its toll on Serena’s marriage and on Natalie, her Canadian-born daughter’s identity and selfhood. What this duo brings to light is that despite the emotional toll migration takes on families, their relationship has been a constant driving force. It continues, to this day, to sustain, inspire, and buoy them as they chart new paths and adventures in their roles as women, daughters, wives, mothers, grandmothers, teachers and life-long learners.

Part II: The Ones Who Leave… The Ones Who Are Left

4. The Geography of Separation

Grace Aneiza Ali

In ‘The Geography of Separation,’ Grace Aneiza Ali writes about women and girls who have known both spectrums of the migration arc: to leave and to be left. The essay is a travelogue, composed of four vignettes, each focusing on a woman or girl Grace encountered in a precise moment in time and in a particular place—Guyana, India, and Ethiopia. Each abstract is framed as an ‘Arrival’ or ‘Departure’ to situate the author’s accountability to these places and to the ways she entered into or departed the lives of the people who live there. Twenty-five years after her first departure from Guyana and many miles circling the globe since, all roads still seem to lead back to Guyana. Whether Grace is in Hyderabad or Harrar or Harlem, she finds herself weaving the stories of these places and the people she has encountered with those of Guyana. For now, this is how she psychically returns. And yet she know it is not enough. In her collection of memoir-essays, Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work, the Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat examines what it means to write stories about a land she no longer lives in. ‘Some of us think we are accidents of literacy,’ she says. Each time Grace boards a plane for another far-off land, she grapples with the guilt that it is not bound for Guyana. She is haunted by the what-ifs. What if I had stayed? What kind of stories should I be telling of Guyana? What do I owe this country? Am I guilty, too, of forgetting?

5. Transplantation

Dominique Hunter

Guyanese-born artist Dominique Hunter, based in the nation’s capital city of Georgetown, moves in and out of several geographic spaces within the Caribbean and North America for various artist residencies and opportunities. They are what she calls ‘mini migrations.’ Yet, she is vocal about rooting her artistic practice in Guyana, even while it is subjected to the ebb and flow of departure. In her art essay, ‘Transplantation,’ Hunter tells us that from a very young age, the Guyanese citizen is indoctrinated with the charge to leave their country. ‘There is an expectation once you have reached a certain age: pack what you can and leave. I am well past that age, yet I remain, stubbornly rooted in the land my parents spent their lives cultivating,’ she writes. What a spectacular thing for any citizen of any place to grapple with—to be, from birth, dispossessed of one’s own land. As both artist and citizen in Guyana, we are shown how she shoulders the personal, political, and economic consequences of Guyanese leaving their native land in droves. In her essay, Hunter uses a dictionary definition of ‘transplantation’ as a metaphorical device to engage ideas of migration and rootedness. She shepherds us through what she deems, ‘A guide to surviving transplantation and other traumas.’ In both her words and collages, Hunter layers organic imagery reminiscent of Guyana’s lush vegetation found in its interior Amazon as well as on its riverbeds and the famous Sea Wall on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Embedded in her visual imagery is a silhouetted self-referential figure. Its haunting presence among the flora and fauna thrives amidst Guyana’s extreme elements of temperature wind, water, and sand. In this symbolic artistic gesture, Hunter insists that the act of staying, of being rooted, of choosing not to be transplanted, is its own kind of agency.

6. Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women

Khadija Benn

Khadija Benn is among the few women photographers living in Guyana and choosing to forge an artistic practice. As a geospatial analyst, Benn often journeys across Guyana to remote places where most Guyanese rarely have access. These small villages are central to Benn’s stunning black and white portraits of the elder Amerindian women who call these communities home. However, as she emphatically notes in her portraiture essay, ‘Those Who Remain,’ these are not invisible women. Benn’s adjoining excerpts from her interviews with the Amerindian elders illustrate how essential they are to Guyana’s history and its migration stories. These women, whose dates of birth begin as early as the 1930s, have witnessed Guyana evolve from a colonized British territory, to an independent state, to a nation struggling to carve out its identity on the world stage, to a country now burdened by its citizens departing. They have also been the ones most impacted by serious economic downturns over the past decade where the decline of mining industries, coupled with very little access to education beyond primary school, have left these communities with few or no choices to thrive. These elder Amerindian women are mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers whose descendants have migrated to border countries like Venezuela and Brazil in South America, to North America, and to nearby Caribbean islands. Yet, these women have made the choice to stay. While their children go back and forth between Guyana and their newfound lands, many of these elders have never left Guyana, some have never left the villages they were born in, and some have no desire to leave.

7. When They Left

Ingrid Griffith

At the age of seven, Ingrid Griffith’s parents left Guyana for the United States, leaving their children in the care of their grandmothers. Griffith’s experience is common for many Guyanese as well as Caribbean families where parents must make the difficult choice to migrate and leave their children with extended family members or caregivers. It is indeed a noble agenda, as Griffith writes about her parents’ goals to work hard in a foreign land so that they can acquire the funds, passports, and visas to have their children join them later in the United States—a process that took years. Told uniquely through Griffith’s perspective as a young girl, ‘When They Left’ offers a glimpse of how a child struggles to reconcile her parents’ love with their simultaneous departure. In her moving memoir essay, Griffith explores the rupture migration enacts on families when children are split apart from their parents and how that separation reverberates years after the first moment of departure. It is the narrative we rarely see—what the act of leaving means for a child and how it becomes an open wound of abandonment.

Part III: Transitions

8. So I Pick Up Me New-World-Self

Grace Nichols

The space between departure and arrival is a terribly fragile one. As Grace Nichols pinpoints her first flight—her precise moment of leaving Guyana—she unravels how that singular moment of departure changed the course of her life forever. Her essay, ‘So I Pick Up Me New-World-Self,’ punctuated with poems ignited by her early years after her arrival in England, details the days when she embarked on the work of inventing the woman and writer she hoped to become. Within both her poems and her reflections, is a similar refrain for women who migrate: our acts of leaving are rarely, if ever, about desire. Instead, they are acts of necessity. Nichols likens her departure to a kind of rupturing, a severing. And then she is confronted with the shock of arrival and the stain of unbelonging thrust on her. As a Guyanese-born woman who has now lived in the United Kingdom longer than she has lived in her homeland, Nichols charts how we leave our old-world self to fashion, in her words, our ‘new-world self.’

9. Revisionist

Suchitra Mattai

Throughout her oeuvre, artist Suchitra Mattai artistically reimagines and disrupts idealized landscapes. Her migratory path through three countries, Guyana, Canada, and the United States, informs her artistic practice, characterized by what she deems ‘disconnected “landscapes” that are unreal but offer a lingering familiarity.’ In the selection of work featured in her art essay, ‘Revisionist,’ Mattai uses landscapes as both a symbolic device and a canvas to illustrate the liminal space of disorientation when one transitions through multiple cultural spheres. Mattai invokes a migration story started long before she left Guyana—that of her Indian ancestors brought by the British from India to the Caribbean, beginning in the 1830s and throughout the early 1900s, to work as indentured servants on British Guiana’s sugar cane plantations. Mattai’s landscapes, used to explore her relationship to the idea of homelands in transition, teem with texture, materiality, and laborious detail. To make this work, Mattai utilizes a bounty of objects and processes that are hand-done. They are a nod to the Guyanese women in her family who are experts in crocheting, weaving, embroidering, needlepointing, and sewing. With each puncture of embroidery, each woven thread, Mattai centers Indian women and the essential role they have played in three centuries of migration movements in and out of Guyana.

10. Memories from Yonder

Christie Neptune

In her art essay, ‘Memories from Yonder,’ American-born artist Christie Neptune mines childhood memories of her mother, a Guyanese immigrant in New York, and her love of crocheting—a craft popular among Guyanese women (as we also see in Mattai’s essay) and passed down through generations. For Neptune, the art of crocheting becomes a metaphor for the necessary acts of unfurling a life in a past land to construct a new life in a new land. Neptune unpacks her artistic process in making her multi-media installation. She portrays Ebora Calder, a fellow Guyanese immigrant and elder. Like the artist’s mother, Ebora migrated to New York in the late 1950s and represents a generation of Guyanese women who in the past sixty years have been part of the mass migration from Guyana to New York City. In the installation, Neptune features a diptych of Ebora that has been distorted and obscured as well as a pixelated short video. In both photograph and video, Calder can be seen quietly engrossed in the slow, methodical, rhythmic act of crocheting a red bundle of yarn. ‘The gesture serves as a symbolic weaving of the two cultural spheres,’ writes Neptune, ‘to reconcile the surmounting pressures of maintaining tradition whilst immersed in an Americanized culture.’

11. A Trace | Evidence of Time Past

Sandra Brewster

In ‘A Trace | Evidence of Time Past,’ Canadian-born artist Sandra Brewster elevates the voices of the matriarchs in her family. Brewster’s family history of migration from Guyana beginning in the 1960s—a decade in which the country saw a tremendous exodus to Canada—parallels the emergence of Toronto as a prominent node in the Caribbean diaspora and one of the largest and oldest Guyanese populations outside of Guyana. As a daughter of immigrant parents, Brewster grew up hearing her family’s stories of life in Georgetown—stories that simultaneously gave her a connection to Guyana as well as left her with questions. In her art essay, she generously mines those questions and offers us the stories, memories, and language of her grandmother, mother, sister, aunts, and cousins whose words simultaneously trace a rupture and chart a chronology: What did it take to leave a beloved Guyana and build a life in an uncertain Canada? As Brewster documents that process, what is revealed is that it takes generations, it takes a whole family, it takes the driving force of women to get to a place of not merely surviving and adapting, but thriving.

Part IV: Returns, Reunions, and Rituals

12. Concrete and Filigree

Michelle Joan Wilkinson

‘What gets left when we migrate?’ is the question American-born curator Michelle Joan Wilkinson poses as she opens her curatorial essay, ‘Concrete and Filigree.’ Within that initial question, we are left to ponder its subtext: What are the objects we choose to carry when we leave a place? How do we decide, when we leave a homeland, which of our possessions become worthy to migrate with us? Writing from a curatorial perspective, Wilkinson explores two deeply personal objects that engage this duality of what we leave and what we carry. Concrete and filigree function as inheritances that connect Wilkinson to her grandfather and grandmother, and, by extension, to Guyana. A concrete house built by her grandfather literally roots Wilkinson in Guyana’s soil; and a treasure trove of gold filigree jewelry passed down to generations of Wilkinson women is a reminder of her family’s traditions. While noting the tremendous responsibility of caring for the things we either inherit or carry with us from our homelands, Wilkinson’s essay reminds us that in small and grand ways, we are all the caretakers of our family’s stories.

13. A Daughter’s Journey from Indenture to Windrush

Maria del Pilar Kaladeen

Maria del Pilar Kaladeen opens her memoir-essay, ‘A Daughter’s Journey from Indenture to Windrush,’ with the passport portrait page of her father Paul Kaladeen. The black and white portrait is stamped in 1961, the year Paul left British Guiana for the United Kingdom. He would return some forty-five years later with his daughter. The passport photo is a document of agency, of one’s freedom, or lack thereof, to move about the world. The portrait of Kaladeen’s father, taken in a moment of great transition for a young man, is full of possibility and promise. Yet, for many decades after his migration, there was silence about his homeland. Without a sense of her family’s roots to ground her identity in, Kaladeen writes of the racism she endured growing up in the United Kingdom as a daughter of immigrants and the pressures, including from her parents, to shirk her cultural identity and be monolithically ‘British.’ It was Kaladeen’s desire to know the land of her father’s birth that served as the catalyst to end his four-decade estrangement from Guyana. Their intertwined story illustrates the fractures and fissures migration creates in relationships and simultaneously, the sheer willpower required to rebuild a bridge between two lands and between a father and daughter.

14. Keeping Wake

Maya Mackrandilal

To create the body of work ‘Keeping Wake’ featured in her art essay, American-born artist Maya Mackrandilal journeyed to Guyana in 2011. She returned to the rice fields where her Guyanese-born mother grew up, until she too left as a young woman. We find Mackrandilal in the midst of loss and death as rituals and preparations are made for her grandmother’s funeral. Water is a key symbol throughout ‘Keeping Wake.’ Mackrandilal paints vivid scenes that mirror the crossing of the kal pani—Hindi for ‘dark waters’—conjuring the traumatic voyage of Indian indentured laborers from India to British Guiana. We are reminded that the history of the Indian crossing into Guyana is a dark one. Indeed, contributors Suchitra Mattai and Maria del Pilar Kaladeen also poignantly link their migration stories to their Indian family legacies. Between 1838 and 1917, over 500 ship voyages deposited more than a quarter-million men and women from India to British Guiana’s Atlantic coast. They would spend over eight decades toiling on sugar plantations and rice fields. Mackrandilal connects generations of those who ventured into the kal pani two centuries ago with those who embark on symbolic crossings of their own twenty-first-century dark waters. The rupture created by the initial crossing of the kal pani remains pervasive. It now haunts a second wave of migration, this time from Guyana to the United States. As she contemplates the past, questioning why the majority of the indentured laborers never returned to India, Mackrandilal draws comparisons to the distance she and her mother now experience with Guyana and reflects on their absence in their homeland. She ponders an important question for us all in the poignant narration of her 2014 video work, Kal/Pani, ‘Acres of rice farm in a country we rarely visit […] what are we, the generation that exists in the wake of estrangement, to make of the pieces?’

Grace Aneiza Ali

Grace Aneiza Ali is a Curator and an Assistant Professor and Provost Fellow in the Department of Art & Public Policy at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University in New York City. Ali’s curatorial research practice centers on socially engaged art practices, global contemporary art, and art of the Caribbean Diaspora, with a focus on her homeland Guyana. She serves as Curator-at-Large for the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute in New York. She is Founder and Curator of Guyana Modern, an online platform for contemporary arts and culture of Guyana and Founder and Editorial Director of OF NOTE Magazine—an award-winning nonprofit arts journalism initiative reporting on the intersection of art and activism. Her awards and fellowships include NYU Provost Faculty Fellow, Andy Warhol Foundation Curatorial Fellow, and Fulbright Scholar. She has been named a World Economic Forum ‘Global Shaper.’ Ali was born in Guyana and migrated to the United States with her family when she was fourteen years old.

Khadija Benn

Khadija Bennwas born in Canada to Guyanese parents and currently lives and works in Guyana as a geospatial analyst. She is a faculty member of the Department of Geography at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Guyana. Her research focuses on digital cartography, community development, and place attachment. As a self-taught photographer, her practice is formed around portraiture and documentary work. Her images have been exhibited at Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art (USA), CARIFESTA XIII (Barbados), the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (USA), and Addis Foto Fest (Ethiopia); and featured in ARC Magazine and Transition Magazine.

Sandra Brewster

Sandra Brewsteris a Canadian visual artist based in Toronto. Her work explores identity, representation and memory, and centering Black presence. The daughter of Guyanese-born parents, she is especially attuned to the experiences of people of Caribbean heritage and their ongoing relationships with their homelands. Brewster’s work has been featured in the Art Gallery of Ontario (2019-2020), she is the 2018 recipient of the Toronto Friends of the Visual Arts Artist Prize and her exhibition It’s all a blur… received the Gattuso Prize for outstanding featured exhibition at the CONTACT Photography Festival 2017. Brewster holds a Master of Visual Studies from the University of Toronto. She is represented by Georgia Scherman Projects.

Erika DeFreitas

Erika DeFreitaswas born in Canada. Her mother migrated from Guyana to Canada in 1970. As a Scarborough-based artist, her practice includes the use of performance, photography, video, installation, textiles, works on paper, and writing. Placing an emphasis on process, gesture, the body, documentation, and paranormal phenomena, she works through attempts to understand concepts of loss, post-memory, inheritance, and objecthood. DeFreitas’ work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. She was the recipient of the TFVA 2016 Finalist Artist Prize, the 2016 John Hartman Award, and longlisted for the 2017 Sobey Art Award. DeFreitas holds a Master of Visual Studies from the University of Toronto.

Ingrid Griffith

Ingrid Griffith,writer and actor, migrated to the United States from Guyana as an adolescent in 1974. Her experiences as a child in Guyana and an immigrant in the United States have formed the wellspring of her creative inspiration. Griffith has appeared in Off-Broadway theatrical productions in classical and contemporary roles. In 2014, she debuted her first solo show at Manhattan International Theater Festival. The award-winning and internationally successful, Demerara Gold, is about a Caribbean girl’s immigrant experience; Demerara Gold was published by NoPassport Press in 2016. Griffith’s recently crafted solo show, titled Unbossed & Unbowed, explores the life of Shirley Chisholm, the first Black Congresswoman in US history. In March 2020, Unbossed & Unbowed debuted at Hear Her Call Caribbean-American Women’s Theater Festival where Griffith won an award for Outstanding Playwriting. Griffith teaches Public Speaking and Theater History at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. The chapter included in this anthology will be part of her soon to be finished memoir.

Natalie Hopkinson

Natalie Hopkinson, PhD, is the Canadian-born daughter of Serena Hopkinson. She is an Assistant Professor in the doctoral program of the Communication, Culture and Media Studies department at Howard University, a fellow of the Interactivity Foundation, and a former editor, staff writer, and culture and media critic at TheWashington Post and The Root. Her third book of essays, A Mouth is Always Muzzled (2018) is about contemporary art and politics in Guyana. She lives with her family in Washington, DC.

Serena Hopkinson

Serena Hopkinson is a retired accountant and arts administrator, and a graduate of Florida Atlantic University. She grew up on the Pomeroon River in Guyana. She is a mother of four, grandmother of six, and a fierce competitor on the tennis court.

Dominique Hunter

Dominique Hunteris a multi-disciplinary artist who lives and works in Guyana, where she was born. Her artistic practice critiques the (non)-representation of Black female bodies in art history and stereotypical portrayals in contemporary print media. Her recent work has expanded to include strategies for coping with the weight of those impositions by examining the value of self-care practices. Hunter has exhibited both in the Caribbean and in the US. She has been an Artist-in-Residence with Caribbean Linked IV and the Vermont Studio Center, where she was awarded the Reed Foundation Fellowship.

Maria del Pilar Kaladeen

Maria del Pilar Kaladeenwas born and currently lives in London. She is an Associate Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in London working on the system of indenture in Guyana and its representation in literature. Having left school at fifteen and returned to education as an adult, she went on to receive a PhD in English Literature from the University of London in 2013. She is the co-editor of We Mark Your Memory (2018), the first international anthology on the system of indenture in the British Empire. Her life-writing has been published in Wasafiri and the anthology Mother Country: Real Stories of the Windrush Children (2018), which was longlisted for the Jhalak Prize in 2019.

Maya Mackrandilal

Maya Mackrandilal is an American-born transdisciplinary artist and writer based in Los Angeles. Mackrandilal holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she was a recipient of a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship, and a BA from the University of Virginia, where she was a recipient of an Auspaugh Post-Baccalaureate Fellowship. Her artwork has been shown nationally, including the Chicago Artists Coalition (where she was a HATCH Artist-in-Residence), Smack Mellon, THE MISSION, Abrons Art Center, The Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, and the Armory Center for the Arts. She has presented artwork and research at national conferences, including the College Art Association, Association for Asian American Studies, the Critical Mixed Race Studies Association, and Open Engagement. Her writing, which explores issues of race, gender, and labor, has appeared in a variety of publications, including The New Inquiry, Drunken Boat, contemptorary, Skin Deep, and MICE Magazine.

Suchitra Mattai

Suchitra Mattaiwas born in Guyana in 1973 and first migrated to Canada with her family in 1976 before they came to the US. Mattai received an MFA in painting and drawing and an MA in South Asian art, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Her work has appeared in various online and print publications such as Hyperallergic, Document Journal, Cultured Magazine, Wallpaper Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, Entropy Magazine, The Daily Serving, and New American Paintings. Mattai has been exhibited nationally and internationally including at the Sharjah Biennial 14, State of the Art 2020 at Crystal Bridges Museum/the Momentary, Denver Art Museum/Biennial of the Americas, Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, the Center on Contemporary Art Seattle, and the Art Museum of the Americas, among others.

Christie Neptune

Christie Neptuneis an interdisciplinary artist working across film, photography, mixed media and performance arts. Her family migrated from Guyana to New York. Neptune holds a BA from Fordham University, New York City. Her films and photography have been included in shows at BASS Museum, Miami (2019); the University of Massachusetts Boston (2018); Rubber Factory, New York (2017); A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, New York (2016); and Rutgers University (2015) among others. She has been featured in publications including Artforum, Hyperallergic, JuxtapozeMagazine, and The Washington Post. Neptune has been awarded the More Art Engaging Artist Residency, The Hamiltonian Gallery Fellowship, The Bronx Museum of the Arts: Artist in Marketplace (AIM), Smack Mellon Studio Residency through the New York Community Trust Van Lier Fellowship, The New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Fellowship, and The NXTHVN Studio Fellowship. Neptune is currently an Artists Alliance Inc. LES Studio Program Artist-in-Residence.

Grace Nichols

Grace Nicholswas born and educated in Guyana. Since migrating to England in 1977, she has written award-winning poetry collections and anthologies for both adults and children. Her first collection, I is a Long Memoried Woman (1983) won the 1983 Commonwealth Poetry Prize. Other poetry collections include, The Fat Black Woman’s Poems (1984), Sunris (1996)—which won the 1997 Guyana Poetry Prize—and Startling the Flying Fish (2005), are all published by Virago. Her adult novel, Whole of a Morning Sky (1986) isset in Guyana. Her poetry collections Picasso, I Want My Face Back (2009), I Have Crossed an Ocean: Selected Poems (2010), The Insomnia Poems (2017), and the most recent, Passport to Here and There (2020), are all published by Bloodaxe Books. Nichols was the Poet-in-Residence at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados and at the Tate Gallery, London, 1999-2000. She received a Cholmondeley Award for her work and an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Hull. She is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Keisha Scarville

Keisha Scarville was born to Guyanese parents who migrated to the US in the 1960s. She is a photo and mixed media artist based in Brooklyn, New York and Adjunct Faculty at the International Center of Photography. Her work has been exhibited at the Studio Museum of Harlem, Rush Arts Gallery, BRIC, Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Diasporan Arts, and The Brooklyn Museum of Art. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, TheVillage Voice, Hyperallergic, Vice, and Transition, among others. Scarville has been awarded various residencies, including from the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Vermont Studio Center, and Baxter Street CCNY.

Michelle Joan Wilkinson

Michelle Joan Wilkinson, PhD, is a writer and curator of Guyanese descent. As a Curator at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, she works on projects related to contemporary Black life and architecture and design. In her previous roles, she curated over twenty exhibitions, including two award-winning shows: For Whom It Stands: The Flag and the American People and Material Girls: Contemporary Black Women Artists. Wilkinson holds a B.A. from Bryn Mawr College and a PhD from Emory University. In 2012, she was a fellow of the Center for Curatorial Leadership, for which she completed a short-term residency at the Design Museum in London. From 2019–2020, she was a Loeb Fellow at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Above adapted from: OneBook Publishers